After my own studies and discussions with Grok xAI, I’ll outline a step-by-step breakdown of modern science. Some still believe science is rational, deductive, and logical. We’ll dissect the process and reveal it’s anti-logical from start to finish, despite using modus tollens.

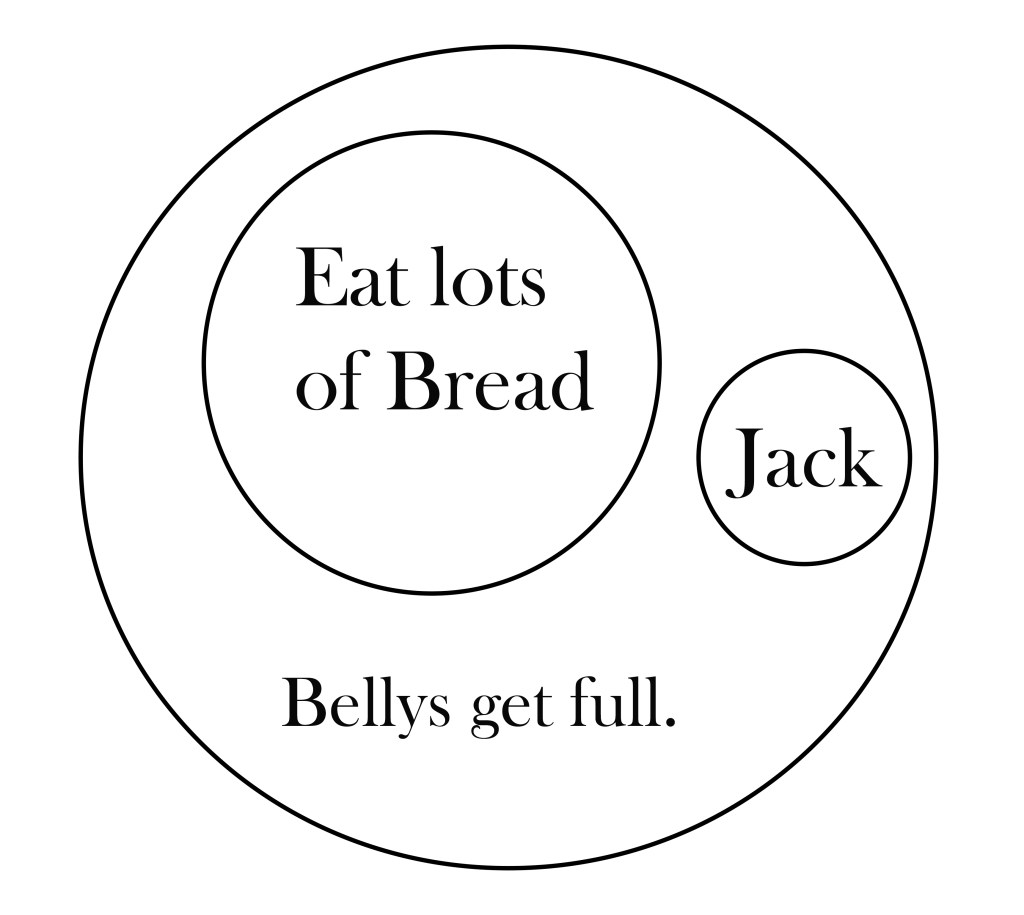

Karl Popper exposed the anti-logical nature of scientific experimentation, particularly the nonsense of affirming the consequent. To counter induction’s irrationality and this fallacy, Popper proposed scientists use modus tollens to invalidate hypotheses. Modus tollens is a valid deductive form. Yet, if you lack upfront truth, affirming the consequent is the only way to positively affirm a claim, if the logic is to correctly correspond to your actions. Popper aimed to minimize this by favoring deduction. The catch? At best, modus tollens can say something is wrong—it can’t confirm truth. Today, top scientists recognize induction and science’s irrationality, leaning into falsification for better experiments.

If we admit science offers no truth, only pragmatic usefulness, then adding modus tollens at the end enhances practical outcomes. We support this. As noted, science fulfils God’s command to dominate the world for practical benefits—a blessing He ordained. But that’s all science is. Even when its utility seems impressive, its statements about reality are false.

Since the scientific process is rooted in inductive and observational fallacies, it’s irrational and anti-logic. Slapping modus tollens on the end doesn’t erase this irrationality; it just improves pragmatic results. It’s right to acknowledge science’s baked-in anti-logic and compensate with deduction—if we clarify this is for usefulness, not knowledge.

Before detailing the process, let’s define falsification. Grok xAI (2024) put it this way:

“The origin of falsification, per Popper, is rooted in the idea that a hypothesis must be scientific if an experiment or observation could prove it false. This was a direct jab at the inductivists and verificationists of his time. Popper’s philosophy was like saying, ‘Science isn’t about piling up evidence for your theory; it’s about daring it to fail.’”

This is accurate but needs unpacking to avoid confusion. Popper critiqued scientific experimentation (i.e., “verification”) that relied wholly on affirming the consequent to link hypotheses to reality.”

Grok calls it a “jab at inductivists,” which can mislead. Even with modus tollens, science remains overwhelmingly inductive. Though Popper shifted “verification” to the “pre-hypothesis” stage rather than the endpoint, falsification swims in a sea of inductive reasoning and observation. Grok was correct that “Popper would have it… it must be possible to conceive of an experiment or observation that could prove it false.” Popper’s falsification operates within “inductive observation” and “inductive experiment.”

Thus, despite jabbing inductivists, Popper’s method still employs induction. Science isn’t one thing—it’s a process. I once heard a scientist claim, “Science is only deductive because it’s only about falsification, specifically modus tollens.” This misrepresents Popper’s approach, which integrates induction and observation. When I asked Grok (2024), it responded, “Absolutely not! Popper argued a theory must be falsifiable, aligning with modus tollens’ deductive logic to disprove it. But induction isn’t sidelined:

- Initial Phase: Science starts with observation and inductive reasoning to form hypotheses.

- Ongoing Nature: As hypotheses are tested, scientists refine them with new observations and inductive leaps, keeping induction central.”

Since falsification uses induction, it’s inherently irrational, violating the laws of identity and contradiction. It’s a systematic affirmation of false premises in unsound arguments, pretending to deny something.

Calling “science deductive” is false. I wouldn’t even say it’s inductive and deductive—its “deduction” is unsound. I wouldn’t label an unsound argument deductive unless we’re pretending in a fantasy world. Generously, we could call science heavily inductive with some deduction tacked on.

This matters for Christians. The Bible uses only sound arguments, rejects induction’s anti-logic, and shows our observations can be wrong. It dismisses empirical observation and induction for knowledge. Thus, falsification isn’t a biblical standard and can’t yield knowledge. Some fools hybridize this irrational human method with the Bible’s rational approach, claiming falsification aids understanding Scripture and truth. This is blasphemy—melding the irrational with God’s rational system defames His mind as irrational or endorsing irrationality. Similarly, fake presuppositionalists claim the Bible ratifies observation and empiricism for knowledge—nonsense.

Another reason to reject falsification: its maxim—“something must be provably wrong to have credibility”—is false. The law of contradiction (LoC) isn’t falsifiable; denying it requires using it. Self-authenticating truths, like the LoC, render falsification inapplicable. At best, falsification fits inductive observations. The Bible, as shown in epistemology, is self-authenticating—unfalsifiable. It can’t be proven wrong because any attempt presupposes it; Scripture declares itself true and all else false. We don’t use falsification to read the Bible or find truth. If it’s such a great rule for Christians, why doesn’t its maxim apply to Scripture?

Note the maxim says “for credibility,” not “to prove true.” Falsification is negative—it can’t produce positive claims without violating logic. Since the Bible rejects observation, empiricism, and induction for knowledge, and falsification uses them, Christians don’t employ it for knowledge. Even using modus tollens—directly, in reductio ad absurdum, or falsification—is only negative, offering no positive truth. When someone says, “I don’t see God healing today,” it’s wrong not because of falsification but because Scripture rejects inductive observation outright.

There’s nothing wrong with modus tollens to show something is false—Scripture uses this deduction. St. Augustine and Paul (1 Corinthians 15) did too, free of empiricism or observation assumptions. But if someone uses empiricism as a standard, showing documented healings should convince them if they’re consistent. We can use modus tollens to refute them with their own flawed epistemology. The catch? Induction’s conclusions don’t logically follow premises, so they can reject evidence due to its inherent uncertainty. Even a deductive argument using observation—ours or theirs—becomes unsound, leaving conclusions skeptical. Induction offers no logical binding to accept any conclusion—you can dismiss or embrace as you please.

As a Christian, the Bible says God heals, and on faith’s demand, He will (John 15: Jesus predestined us to ask and receive). I expect healings. My observations are private knowledge—and if I applied these with deductions from Scripture “for myself,” then my self-knowledge is what the bible asserts. But shifting private to public knowledge violates logic’s laws. Scripture alone is our starting point for knowledge about healing. Anyone using inductive observations to argue miracle healing is a fool, rejecting the Bible as the sole epistemic foundation.[1] Such debates aren’t about healing but epistemology—Scripture’s deductive logic versus induction’s fallacy. Tell them they’ve abandoned Christian doctrine on knowledge and logic; if they don’t repent, boycott and excommunicate them.

The Scientific Process

Observation and Hypothesis Formation (Inductive Step)

Note: “Scientific experimentation (affirming the consequent)” has been pushed back to “hypothesis formation.”

Scientists observe phenomena in nature or data, noticing that when event A occurs, phenomenon B follows. This resembles affirming the consequent: “If A, then B; B happens, so A caused it.”

- Example 1: (A) Rain occurs, (B) my yard gets wet. (B) I see my yard wet, so I hypothesize (A) it rained.

- Example 2: (A) Bacteria add chemical X to solution H, (B) it turns red. (B) I see it red, so I hypothesize (A) bacteria added X.

Formulating the Hypothesis (Setting Up for Modus Ponens)

Initially, scientists observe B (a fallacy) to check their idea. If testing’s possible, they run preliminary affirming-the-consequent experiments for merit. Then, they frame hypotheses as modus ponens: “If A, then B; A, thus B.” They pretend a necessary connection exists to apply modus tollens later—not to affirm the consequent but to predict outcomes. They say, “If hypothesis (A) is true, under these conditions, we’ll see (B).”

In layman’s terms, this is logical voodoo, a void, or superstition.

Two ways this bait-and-switch happens:

- Vincent Cheung’s Example (A Gang of Pandas):

- “If (A) is a cause, then (B) is a result. B happens, thus A caused it.”

- Restated as modus ponens with B and A flipped, using a false conclusion to build an argument.

- Direct Pretence: Pretending inductive “If A, then B” is real or pretend it’s a necessary connection. This is like misstating a math problem to reflect reality. If I buy 4 apples at $1 each, calling it calculus is delusional if it doesn’t match reality. Scientists engage reality via affirming the consequent due to observation—they can’t avoid it. Restating it as modus ponens is delusional because it doesn’t mirror their actual interaction with phenomena.

Experimental Design (Testing via Modus Ponens)

Scientists design experiments controlling A to see if B follows, mimicking modus ponens:

- If hypothesis A is true, under specific conditions, B occurs (If A, then B).

- They ensure A is present.

- They check if B happens (A leads to B).

This isn’t just to affirm the hypothesis (a fallacy) but to test predictions under control. Yet, problems still abound: - The setup stems from a fallacy—using a false conclusion from observation and affirming the consequent to fake a connection. This restated logic doesn’t reflect their real-world engagement; it’s fabricated.

- They only pretend it’s modus ponens—in name only. Some admit the connection is merely sufficient, making falsification tentative, not necessary, contradicting the very definition of logical inference.

- Controlled tests can’t rule out infinite unknowns (e.g., heat affecting results unbeknownst to a scientist ignorant of it).

Vincent Cheung notes, “The idea is simple. To know that any experiment is “constructed properly” the scientist’s knowledge must be “bigger” than the experiment. But if his knowledge is already “bigger” than the experiment, then he hardly needs to perform the experiment to gain knowledge that is limited by the experiment. The only way to be sure that one has identified and controlled all variables that may affect the experiment is to possess omniscience. The conclusion is that only God can tell us about the universe.”[2]

Falsification Attempts (Modus Tollens)

Here’s the shift:

- If B doesn’t occur when A is present: “If A, then B; not B, therefore not A” (hypothesis falsified).

Scientists aim to confirm hypotheses (affirming the consequent), but better ones seek disproof. Misaligned results falsify, and this leads to rethinking and refinement.

Yet observation and affirming-the-consequent thinking build the argument for falsification. Induction underpins science’s foundation and definition. The “deductive” arguments are unsound—born from false conclusions, misrepresenting reality. It’s deduction by pretence. Before falsification, the hypothesis’s necessary connection is unknown. Falsification deems it wrong, which says little.

The experimental connection has two interpretations: - If honest (connection is sufficient or a guess), falsification is uncertain, not necessary—violating deduction’s essence.

- If claiming necessity, it’s pretence, falsifying only a pretend reality, breaching contradiction and identity laws.

- Finally, saying “laws are formulated by falsification” is a non-sequitur. Negative propositions can’t yield positives without adding information—violating logic. Laws from falsification can only say “this isn’t that.” Positive laws from falsification defy logic; negative isn’t positive.

The point is that observation and affirming the consequent thinking and testing is involved in formulating the argument that will be tested by falsification. Thus, induction is both the foundation of science and therefore involved in the definition of science. The so-called deductive arguments are unsound, because they are created by false conclusions and the logic does not reflect their interaction with reality. It is deduction only by pretending. Before falsification is used, it is not known if the major premise of the syllogism (hypothesis) has a necessary connection. Falsification says this unsound argument is wrong. which is not really saying that much.

The connection in their experiment can be taken in two ways. If they are honest and admit the connection, at the very best is sufficient or a guess, then if falsification is used, the falsification is only a guess, but not a necessary falsification. This violates the very definition of deduction, which is necessary. If they insist the falsification is necessary, then they violate the laws of contradiction and identity. If they want to insist their connection in their experiment is necessary, then it is only by pretending. Thus, if they use falsification, it is only falsifying a pretend reality.

Lastly, there is the part where scientists say, “laws… are formulated by falsification.” This is false. It is a non-sequitur fallacy. Remember our rules for category syllogisms? We talked about distribution of terms but also the quality and quantity of a syllogism. If the propositions of an argument are negative, you cannot get a positive out of it. The same here. Falsification can only say, this is wrong, but to then turn around and say we have a law that says, “this is this,” is to add more information than what the argument says. Laws, formulated by falsification can only say at best, “this is not that.” Every positive law stated by scientists using falsification is a violation of the laws of logic. To say negative is a positive is anti-logic.

[1] This is different from starting with the truth given by scripture, and then present your healing as “testimony” that agrees with the truth. You are saying the bible is the proof, and my testimony agrees with the truth, not the other way around.

[2] Vincent Cheung. A Gang of Pandas. Sermonettes Vol.1.